| SPACE TODAY ONLINE COVERING SPACE FROM EARTH TO THE EDGE OF THE UNIVERSE | ||||||||||

| COVER | SOLAR SYSTEM | DEEP SPACE | SHUTTLES | STATIONS | ASTRONAUTS | SATELLITES | ROCKETS | HISTORY | GLOBAL LINKS | SEARCH |

|

MONKEYS AND OTHER ANIMALS IN SPACE »

The first men and women who traveled in space — in the 1960s — depended on the sacrifices of other animals that gave their lives for the advancement of human knoweldge about the conditions in outer space beyond this planet's protective ozone layer, about the effects of weightlessness on living organisms, and about the effects of stress on behavior. Preparations for human space activities depended on the ability of animals that flew during and after the 1940s to survive and thrive. Let's look at Russia's space dogs first, then the other animals in space.

Near the end of the 1950s, the U.S.S.R. was preparing to send a dog into orbit above Earth. The Soviets used nine so-called Space Dogs to test spacesuits in the unpressurized cabins of spaceflight capsules. For practice suborbital flights, the dogs Albina and Tsyganka were blasted upward to the edge of Earth's atmosphere at an altitude of 53 miles where they were ejected to ride safely down to Earth in their ejection seats.

Subsequent suborbital flights by the space dogs reached altitudes as high as 300 miles. Then came the stunning 1957 launches of Sputnik 1 and Sputnik 2 to orbit. What is a suborbital flight? »

Laika and Sputnik 2

Scientists in the Soviet Union were sure that organisms from Earth could live in space. To demonstrate that, they sent the world's second artificial space satellite — Sputnik 2 — to space from the Baikonur Cosmodrome on November 3, 1957.

Laika inside Sputnik 2

[Tass News Agency photo via Russian Space Agency]

On board was a live mongrel dog named Laika (Barker in Russian) on a life-support system. Laika also was known as Kudryavka (Little Curly in Russian). The American press nicknamed the dog Muttnik.

While other animals had made suborbital flights, Laika was the first animal to go into orbit. She suffered no ill effects while she was alive in an orbit at an altitude near 2,000 miles.

Laika had been a stray dog — mostly a Siberian husky and around three years old — rounded up from the Moscow streets and trained for spaceflight. She was carried aloft in a capsule which remained attached to the converted SS-6 intercontinental ballistic missile which rocketed her to orbit.

The 1,120-lb. Sputnik 2 was outfitted with scientific gauges, life-support systems, and padded walls, but was not designed for recovery. Laika was supported inside the satellite by a harness that allowed some movement and access to food and water. Electrodes transmitted vital signs including heartbeat, blood pressure and breathing rate.

The American press nicknamed the dog Muttnik. She captured the hearts of people around the world as the batteries that operated her life-support system ran down and the capsule air ran out. Life slipped away from Laika a few days into her journey. Later, Sputnik 2 fell into the atmosphere and burned on April 14, 1958.

Today, Laika again captures the hearts of people with a monument to her erected 40 years after her spaceflight by the Russians to honor fallen cosmonauts at Star City outside Moscow. The likeness of Laika can be seen peeping out from behind the cosmonauts in the monument.

Laika also is remembered on a plaque at the Moscow research center where she was trained.Associated Press article on Laika in New York Times November 3, 1957 »

'Soviet Fires New Satellite, Carrying Dog;

Half-Ton Sphere Is Reported 900 Miles Up;

Orbit Completed — Animal Still Is Alive, Sealed in Satellite, Moscow Thinks'

Tass News Agency photo of Laika in Sputnik 2 »

with RealAudio sound file of Laika

An Internet memorial to Laika »

'The more time passes, the more I'm sorry...'

Later Russian Dogs in Space

During the Sputnik series of satellites, the Russians prepared to send men to orbit by sending dogs first. At least thirteen Russian dogs were launched toward orbit between November 1957 and March 1961.

By order of flight, they were:

Laika (Barker in Russian)

A photo on a postage stamp shows four dogs that flew on three different space missions – Strelka, Chernushka, Zvezdochka, and Belka.

Bars (Panther or Lynx)

Lisichka ( Little Fox)

Belka (Squirrel)

Strelka (Little Arrow)

Pchelka (Little Bee)

Mushka (Little Fly)

Damka (Little Lady)

Krasavka (Beauty)

Chernushka (Blackie)

Zvezdochka (Little Star).

Verterok or Veterok (Little Wind)

Ugolyok or Ugolek (Little Piece of Coal)

Five of the dogs died in flight:

Laika, Bars, Lisichka, Pchelka, and Mushka.

Here are their stories:

Bars and Lisichka

On July 28, 1960 a test flight related to the Vostok spacecraft was launched. The booster exploded during launch and the dogs Bars (Panther or Lynx) and Lisichka ( Little Fox) on board the spacecraft were killed.

Belka and Strelka

Russian dogs Strelka and Belka went into space aboard Sputnik 5 and returned healthy [NASA Archive]

They are preserved at

Memorial Museum of Astronautics »

Korabl-Sputnik-2 (Spaceship Satellite-2), also known as Sputnik 5, was launched on August 19, 1960. On board were the dogs Belka ( Squirrel) and Strelka (Little Arrow). Also on board were 40 mice, 2 rats and a variety of plants.

After a day in orbit, the spacecraft's retrorocket was fired and the landing capsule and the dogs were safely recovered. They were the first living animals to survive orbital flight.

Strelka later gave birth to six puppies, one of which was given to Caroline Kennedy, daughter of U.S. President John F. Kennedy, by Soviet premier Nikita Khrushchev.

Today, the bodies of Strelka and Belka remain preserved at the Memorial Museum of Astronautics in Moscow. Belka sits in a glass case in the museum while Strelka is part of a traveling exhibit that has visited the U.S., China, Australia, Israel and other countries.

Pchelka and Mushka

Space dogs Pchelka (Little Bee) and Mushka (Little Fly) were launched on December 1, 1960 aboard Korabl-Sputnik-3, also known as Sputnik 6. This spacecraft also spent a day in orbit . However, the retrofire burn was not performed with the correct orientation and the capsule reentered the atmosphere at too steep an angle and was destroyed.

Damka and Krasavka

On December 22, 1960 another Korabl Sputnik was launched carrying the dogs Damka (Little Lady) and Krasavka (Beauty). The booster's upper rocket stage failed and the launch was aborted. The dogs were safely recovered after their unplanned suborbital flight.

Kosmos 110 flight record dogs Verterok and Ugolyok

Chernushka and Sputnik 9

Korabl-Sputnik-4, also known as Sputnik 9 was launched on March 9, 1961 and carried the black dog Chernushka (Blackie) on a one orbit mission. Also onboard the spacecraft was a dummy cosmonaut, mice and a guinea pig.

Zvezdochka and Sputnik 10

Korabl-Sputnik-5, also known as Sputnik 10 was launched on March 25, 1961 and carried the dog Zvezdochka (Little Star) and a dummy cosmonaut — a wooden mannequin — on a one orbit mission. This final rehearsal for the Vostok 1 flight was successful. Days later, Yuri Gagarin became the first man in space on April 12, 1961, spending 108 minutes orbiting above Earth in his Vostok 1 capsule.

Verterok and Ugolyok

The biosatellite Kosmos 110 (also known as Voskhod 3) was launched on February 22, 1966 and carried the dogs Verterok or Veterok (Little Wind) and Ugolyok or Ugolek (Little Piece of Coal).

The dogs were to be observed in orbit for 23 days via video transmission and biomedical telemetry. Their spacecraft landed on March 16, 1966 after a 22 day flight.

Theirs still stands as the canine spaceflight record and was not surpassed by humans until the flight of Skylab 2 in June 1974.

Monkeys and Other Animals

A variety of large and small animals — not just dogs — have been flown to space for science experiments in orbit.

Fruit flies were launched on a V2 rocket from White Sands, New Mexico, to the edge of space in July 1946 to study the effects of high-altitude radiation. The rocket reached an altitude of about 100 miles.

How high is high? » Where does space begin? »

Monkeys named Albert

The very first primates ever fired to an altitude near space were the monkeys Albert 1 and Albert 2. They died in 1949 in the nose cones of captured German V-2 rockets during U.S. launch tests.

The V-2 rockets carried Air Force Aero Medical Laboratory monkeys named Albert I, II, III, and IV high in the atmosphere to see how they might withstand space conditions. All of the monkeys survived the upward trip, but were killed when parachutes failed to open and the nose cones impacted the ground.

Yorick and 11 Mice

A monkey and mice died in 1951 when their parachute failed to open after the the U.S. Air Force launched an Aerobee rocket from Holloman Air Force Base in New Mexico.

Later that year — on September 20 — the U.S. Air Force launched the first animal flight near space that ended with a live occupant. The nosecone on the Aerobee rocket carried a monkey named Yorick and 11 mice to a height of 45 miles. Space is said to began at 50 miles. When the animals were recovered alive, it went down in the record book as the first successful flight near space for living creatures.

The last Air Force launch of an Aerobee rocket on — May 22, 1952 — carried two mice named Mildred and Albert, and two Phillipine monkeys named Patricia and Mike. Scientists watched the signal from a video camera in the nosecone to see the effects of acceleration, weightlessness and deceleration as the monkeys and mice flew to an altitude of 36 miles.

To measure effects of 2,000-mile-per-hour acceleration, Mike was strapped in a prone position and Patricia was supported upright in a seated position. The mice were seen floating in a holding drum as they encountered weightlessness. The animals survived the parachute landing. Patricia and Mike lived the rest of their lives at the National Zoological Park at Washington, D.C.

Gordo the Squirrel Monkey

America turned away from preparing for human space flight for half a decade. In those years before NASA, the military focused on missiles as weapons.

Laika re-focused the nation's attention on spaceflight. A year after her launch, the U.S. Army launched a squirrel monkey named Gordo aboard a Jupiter AM-13 booster on a suborbital flight on December 13, 1958. The monkey completed the flight up and down safely. However, during his recovery, a flotation device in the rocketºs nose cone failed and Gordo died.

Monkeys Able and Baker

The U.S. launched two monkeys six months later — a female rhesus named Able and a female squirrel monkey named Baker — aboard a Jupiter AM-18 rocket suborbital flight in 1959. The monkeys flew to an altitude of 300 miles up at speeds over 10,000 mph. The monkeys were weightless for nine minutes. They were recovered successfully. Afterward, sensors that had been used to transmit vital signs data were removed in surgery. During the operation, Able died from the anesthetic.

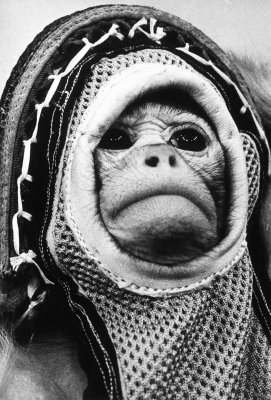

Rhesus monkey suited up for Little Joe launch of Mercury capsule [NASA archive]

Sam and Miss Sam

Mercury capsules atop Little Joe rockets were used to blast the rhesus monkeys Sam and Miss Sam to space. Sam lifted off on December 4, 1959, and traveled 55 miles into space. He tested a Mercury couch and restraint harness that would be used to protect astronauts during high acceleration periods in manned Mercury flights. Sam was recovered alive in the Atlantic Ocean off Cape Hatteras, North Carolina, by the USS Borie. Back in the lab, he reportedly embraced Miss Sam joyfully.

Miss Sam, in turn, journeyed upward in a Mercury capsule on January 21, 1960. However, she flew only to an altitude of nine miles during a 58-minute test of an escape system for future Mercury manned flights. She also was recovered in the Atlantic Ocean, by a Marine helicopter.

A Chimpanzee Ham

Ham was named in honor of Holloman Aerospace Medical Center, New Mexico, where the chimpanzees lived and also in honor of Holloman commander Lt. Col. Hamilton Blackshear. In training for his suborbital flight to space, the four-year-old chimpanzee practiced with three other chimps pulling levers to receive rewards for correct choices. Eventually, Ham was blasted off inside Mercury capsule number 5 atop a Redstone rocket from Cape Canaveral, Florida, on January 31, 1961. His mission was to prove that live animals aboard a spacecraft could carry out their jobs during launch, weightlessness and reentry.

Unfortunately, Ham's rocket overshot and boosted the chimp in his capsule to a speed of 5,857 mph. That was 1,457 mph faster than planned, which resulted in Ham experiencing 1.7 more minutes of weightlessness than projected. He was weightless for a total of 6.6 minutes. The excess power also shot the capsule 122 miles off course. Even so, Ham was able to perform his tasks almost perfectly.

The Mercury capsule landed far outside the Atlantic Ocean target zone at 12:12 p.m., 60 miles from the nearest recovery ship, the destroyer Ellison. Lying on its side in the water, the capsule was battered by waves. Tears in the landing bag capsized the craft. An open cabin pressure relief valve let sea water in. It was beginning to submerge when Navy rescue helicopter pilots found it. At 2:52 p.m. a helicopter managed to snag the craft and lift it and 800 pounds of sea water out of the ocean. After dangling all the way to a ship, the capsule was lowered to the deck. Nine minutes later Ham came out in good condition. He happily accepted an apple and half an orange.

Ham survived in good condition to retire to the National Zoological Park at Washington, D.C., on April 2, 1963. The success of his Mercury capsule flight led directly to the launch of Alan Shepard on America's first human suborbital flight on May 5, 1961.

Enos in Orbit

The first non-human primate in orbit was the chimp Enos launched November 29, 1961, in a Mercury capsule in preparation for manned flight. Enos was said to be the first "living being" sent to orbit by the United States.

Primates are mammals, such as humans, apes, monkeys and lemurs, having large brains, eyes that look forward with a highly developed sense of vision, flexible hands and feet, and usually opposable thumbs they can bend to help pick up objects. Russian cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin became the first primate in orbit when he flew in space in April 1961. Of course, other primates had been sent almost to space earlier and other animals, the Russian space dogs, had been in orbit before Enos or Gagarin.

Enos blasted off atop an Atlas 5 rocket and completed two orbits before being brought down one orbit early because his Mercury capsule was not performing exactly as planned. In even so, Enos successfully performed his jobs in space. After the success of the chimp's flight, John Glenn was launched on February 20, 1962, to become the first American to orbit Earth.

Cats in simulated spacesuits [NASA archive]

Felix the Cat

France launched a black and white stray tomcat of the Paris streets on October 18, 1963, on Veronique AGI sounding rocket No. 47 from the Hammaguir test range in Algeria. Was it a male named Felix. Or a female named Felicette? Whichever, it was the first cat in space as the capsule in the rocket's nose cone separated at 120 miles altitude and descended by parachute. Electrodes in the cat's brain transmitted neurological impulses to a ground station. The cat was recovered. Another cat flight on October 24, 1963, failed and was not recovered. Flights were directed by France's Centre d'Enseignement et de Recherches de Medecine Aeronautique (CERMA).

Biosatellites

The U.S. launched a series of biological capsules to investigate the influence of space flight on living organisms.

Biosatellite I, launched Dec. 14, 1966, was lost when the retrorocket failed to ignite and it could not land.

Biosatellite 2, launched Sept. 7, 1967, was recovered. The scientific payload included 13 biology and radiation experiments exposed to microgravity during 45 hours in Earth orbit. Living things in the biological capsule included insects, frog eggs, microorganisms and plants. The three-day flight was cut short by the threat of a tropical storm in the recovery area and a communication problem between the satellite in orbit and the tracking systems on the ground.

Biosatellite 3, launched June 29, 1969, three weeks before the first men were to land on the Moon. A male pig-tailed monkey (Macaca nemestrina) named Bonnie was the passenger set to orbit in Biosatellite 3 for a month. Unfortunately, Bonnie had to brought down, ill from loss of body fluids, after only 8.8 days. He died shortly after landing on July 7.

Russia, cooperating with the U.S. and European nations, has flown a number of biosatellites in orbit, testing different kinds of plants and animals in weightlessness. The biological test flights have carried white Czechoslovakian rats, rhesus monkeys, squirrel monkeys, newts, fruit flies, fish and others.

Orbiting Frog Otolith

The Orbiting Frog Otolith satellite (OFO-A), launched by the U.S. on Nov. 9, 1970, from Wallops Island, Virginia, on a Scout rocket, carried two bullfrogs (Rana catesbeiana). Biologists wanted a better understanding of the effect of microgravity on the otolith, a sensory organ that responds to changes in an animal's orientation within Earth's gravitational field. The Frog Otolith Experiment Package (FOEP) kept the two frogs alive in orbit. They were housed in a water-filled, self-contained centrifuge which supplied the test acceleration during orbit. The FOEP stayed in orbit for seven days. The satellite was not recovered.

Arabella spider on Skylab-3 [NASA archive]

Arabella, the Orb Weaver

NASA's Skylab 3 space station crew flight on July 28, 1973, carried a student experiment with Arabella, the orb weaving garden spider (Araneus diadematus) for 59.5 days. The spider, which had a distinctive white cross mark on its abdomen, was able to weave the traditional orb web in the near-zero-gravity environment only with practice. Such webs are logarithmic spirals – sometimes incorrectly referred to as concentric circles – of silk threads that are small in the center and larger at the outer area of the web. A spider uses its own sense of its weight to determine the amount of silk to spin into the web, so gravity is important in the construction. The Skylab student experiment observed how microgravity affected Arabella's weight sensing ability.

Bion Satellites

The U.S.S.R. launched a series of biological capsules to investigate the influence of space flight on living organisms. The series of Bion satellites was designed to study the effects of radiation and the space environment on biology. The Bion satellite is modified from a Zenit type of spysat. It is lofted to space by a Soyuz rocket from the Plesetsk Cosmodrome in northern Russia. Bion launches began in 1973. The first Bion carried tortoises, rats, insects, and fungi. Other missions have carried plants, mold, quail eggs, fish, newts, frogs, cells, and seeds. Starting with Bion 6, the missions carried pairs of monkeys.

- Bion 1/Cosmos 605 launched on Oct. 31, 1973, looked into the influence of space flight on living organisms and tested life-support systems for biological entities. The capsule as recovered.

- Bion 2/Cosmos 690 launched Oct. 23, 1974, investigated the upper atmosphere and outer space.

- Bion 3/Cosmos 782 launched Nov. 25, 1975, carried 25 rats and other animals. It was the first time that the United States participated in the Soviet Cosmos Program. Scientists from France, Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Poland, Romania, the U.S. and the U.S.S.R. participated in these investigations.

- Bion 4/Cosmos 936 launched August 3, 1977, carried 30 rats among experiments from the U.S.S.R., the U.S., Czechoslovakia, France, Hungary, Poland, Romania, Bulgaria and the German Democratic Republic. The biosatellite was recovered near Kustanay in Central Asia after orbiting for 18.5 days.

- Bion 5/Cosmos 1129 launched Sept. 25, 1979, carried 37 rats biology experiments in embryo development and radiation medicine from Czechoslovakia, France, Hungary, Poland, Romania, the German Democratic Republic, the U.S. and the U.S.S.R. Experiments included the first attempt to breed rats in space.

- Bion 6/Cosmos 1514 launched Dec. 14, 1983, carried monkeys named Abrek and Bion and several pregnant rats. It was the first U.S.S.R. orbital flight of a non-human primate. More than 60 experiments were performed by scientists from Bulgaria, Hungary, the German Democratic Republic, Poland, Romania, Czechoslovakia, France, the U.S.S.R. and the U.S. American scientists conducted three experiments on the primates and another experiment on the rat subjects. The capsule was recovered.

- Bion 7/Cosmos 1667 launched July 10, 1985, carried monkeys named Verniy and Gordiy. It was the second USSR biosatellite mission with a primate payload. It also featured a large rodent payload. Countries participating in the mission were the USSR, U.S., France, Czechoslovakia, the German Democratic Republic, Poland, Romania, Bulgaria and Hungary. The U.S. conducted only a single experiment cardiovascular experiment on one of the two flight monkeys.

- Bion 8/Cosmos 1887 launched Sept. 29, 1987, carried monkeys named Drema and Erosha, ten rats and other animals.

- Bion 9/Cosmos 2044 launched Sept. 15, 1989, carried 29 U.S. and U.S.S.R. life science experiments conducted on two rhesus monkeys, ten rats, fish, amphibians, insects, worms, protozoans, cell cultures and plants. The monkeys were named Zhankonya and Zabiyaka. It was was the seventh Soviet Biosatellite to orbit the Earth with joint U.S./U.S.S.R. experiments. Hungary, the German Democratic Republic, Canada, Poland, Britain, Romania, Czechoslovakia and the European Space Agency also participated.

- Bion 10/Cosmos 2229 launched Dec. 29, 1992, carried monkeys named Ivasha and Krosha. After 12 days in Earth orbit, the capsule was recovered north of the city of Karaganda. This Cosmos 2229 mission also was referred to as Bion 10, because it was the tenth in a series of Soviet/Russian unmanned satellites carrying biological experiments.

- Bion 11 launched 24 December 1996 carried monkeys named Lalik and Multik.

First Manned Animal Lab in Orbit

NASA began a series of shuttle flights carrying live animals to space with the launch of Challenger flight STS-51B on April 28, 1985. Two squirrel monkeys and 24 albino rats were housed in Spacelab, a reusable space laboratory developed for NASA shuttles by the European Space Agency. Known as Spacelab-3, it actually was the second flight of Spacelab.

Scientists wanted to see if there were any physical and behavior changes brought about by space flight. The adult male monkeys (Saimiri sciureus) and male rats (Rattus norvegicus) were housed in life-supporting cages. They were not restrained and instrument probes were not implanted in the monkeys.

"The two monkeys on Spacelab 3 were purposely not given names. However, if my memory serves me right, they did have numbers which were 385-80 and 3065," according to J.W. Cremin, Spacelab 3 mission manager.

During the flight, both monkeys ate less food and were less active in space than on the ground. One monkey adapted quickly to microgravity. The other exhibited symptoms like the condition astronauts refer to as Space Adaptation Syndrome. That indisposed monkey did not eat and drank little water for four days of flight. On the fifth day, the astronauts hand-fed banana pellets to him and he began to act more like the first monkey.

After Challenger returned to Earth on May 5, 1985, the monkeys and rats were healthy and in good condition. Post-flight tissue analyses were not performed on the flight monkeys. That means they were not killed.

STS-90 swordtail fish [NASA]

Green Tree Frogs

In 1990, a Japanese reporter took green tree frogs to the Mir space station.

Oyster Toad Fish and Crickets

U.S. shuttle Columbia and a crew of seven astronauts launched April 17, 1998, on flight STS-90, a Neurolab mission taking along a menagerie of 170 newborn rats and pregnant mice, 229 tiny swordtail fish, 135 snails, four prehistoric-looking oyster toad fish, and 1,500 cricket eggs and larvae. The animals were in the Spacelab module in Columbia's cargo bay. The seven astronauts studied how the very-low-gravity environment of near-Earth orbit influenced the animals' brains and central nervous systems.

Animals aboard shuttle Columbia's last flight

Columbia flight STS-107 was lost with its crew of seven astronauts on February 1, 2003. Much of the science data gathered during 16 days in orbit was lost. However, NASA was able to harvest some experimental results because the astronauts had beamed their data down by radio while still in space. Other experiments were recovered amidst the debris on the ground.

Surprisingly, hundreds of worms, known as C. elegans, were found alive. They were the only live experiments found. About the size of a pencil point, the worms have a life cycle of 7-10 days. Those found were four to five generations removed from the original worms sent to space in Columbia to test a synthetic nutrient solution.

The shuttle carried other small animals, including silkworms, spiders, carpenter bees, harvester ants, and Japanese killfish. It also carried roses, moss and other plants, as well as bacteria and slime mold.

The moss Ceratodon was flown on Columbia to study how gravity affects cell organization. The moss was sprayed during the flight with a chemical that destroyed its protein fiber. Then formaldehyde was used to preserve the dead moss. Some of the moss was found in the debris.

Tragedy of Space Shuttle Columbia »

Astronauts Rockets Satellites Shuttles Stations Solar System Deep Space History Global Links Top of this page Search STO STO cover Copyright 2004 Space Today Online