Mammoth Hurricanes on the Sun

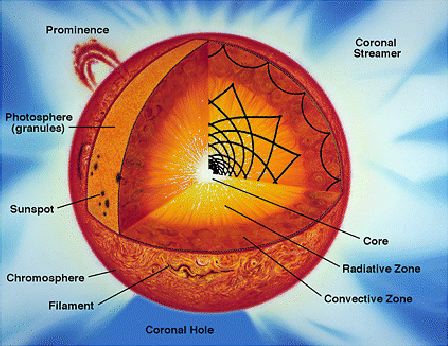

Click to enlarge NASA diagram of the Sun |

They say sunspots act pretty much like planet-sized hurricanes. They are so big and powerful -- pulling in as much material as they spew out -- that they actually seem to override the laws of physics in magnetic fields.

How sunspots sustain themselves has been a riddle for 400 years.

Clumping magnets. Magnetic fields make up the cool dark sunspots on the Sun's surface. Now, solar astronomers at NASA and Stanford University have discovered how those magnetic fields clump together rather than dispersing.

Previously, when they had observed gases flowing from sunspots, they figured it was the result of the various magnetic fields repelling each other like small magnets on Earth repel each other.

However, now they think the outflowing gases are a surface phenomenon that occurs as the sunspot sucks in new material to hold itself together. Looking deep inside, they found planet-sized whirlpools or hurricanes, sucking material inward. That inflow pulls the magnetic fields back together.

Ten times bigger. The pressure inside such a sunspot hurricane is ten times higher than a tropical hurricane on Earth.

Without the sucking in of matter, a sunspot wouldn't last a day. With it, a sunspot can last for weeks. In the end, a sunspot gets torn apart and the researchers wanted to better understand its life cycle. To find out, they used sound waves something like the ultrasound doctors use to capture images of unborn babies.

High speed suction. They discovered that the magnetic field underneath a sunspot can cut off the sunspot¹s supply of energy from the Sun¹s hot core. That plugs the spot. When that happens, matter above the plug cools and becomes more dense. Eventually, it becomes sufficiently heavy for gravity to drag it down into the center of the sunspot. It is sucked in at a speed of 3,000 miles per hour.

As long as the magnetic field remains strong, the cooling effect continues to suck in the gasses that make the structure stable -- a self-perpetuating cycle.

Galileo's drawings. Sunspots have been the object of scientific research for centuries -- at least as far back as the early 17th century when Italian astronomer Galileo Galilei used sunspots to calculate the speed of the Sun¹s rotation. Today, Galileo's hand-drawings of sunspot locations on the Sun are relics beside NASA's 21st century computer-generated multicolored models of sunspots.

| Sun and Sunspots Index Page | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Learn More about Our Sun and Sunspots and Their Effects on Earth |

| Read more Space Today Online stories about the Solar System | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Star: | The Sun | ||||

| Inner Planets: | Mercury | Venus | Earth | Mars | |

| Outer Planets: | Jupiter | Saturn | Uranus | Neptune | Pluto |

| Other Bodies: | Moons | Asteroids | Comets | ||

| Beyond: | Pioneers | Voyagers | |||

| Top of this page | Solar System index | Space Today Online cover |