|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

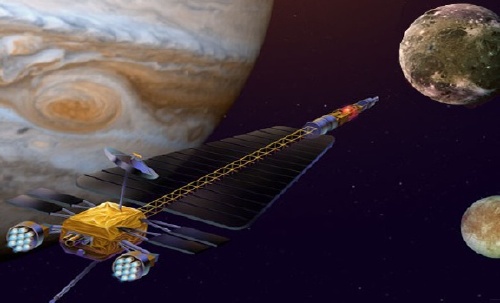

| EXPLORING THE JUPITER SYSTEM | |||||

| Jupiter | Moons | Oceans | Volcanos | Rings | Radio |

| JIMO | Galileo | Cassini | Pioneer | Voyager | Resources |

Jupiter is Like a Mini Solar System

with At Least 61 Moons Orbiting the Planet

CALLISTO » IO » EUROPA » GANYMEDE » AMALTHEA » MOONS OF THE SOLAR SYSTEM »

Jupiter, the fifth planet outward from the Sun, is the largest planet in our Solar System. In fact, Jupiter has something like a whole planetary system of its own, with spectacular rings and the most moons of any planet, according to astronomers looking at the planet through the Canada-France-Hawaii Telescope atop the dormant volcano Mauna Kea on the island of Hawaii.

The largest moon in the Solar System is Ganymede with a diameter of 3,280 miles, even larger than either of the planets Mercury and Pluto.

A moon is a natural satellite rotating around a planet. Each moon is much smaller than its planet. Only Mercury and Venus do not have any moons. By comparison with Jupiter, Earth has only one moon and Mars has two.

List of moons for each planet »»

Io I 1610 Europa II 1610 Ganymede III 1610 Callisto IV 1610 Amalthea V 1892 Himalia VI 1904 Elara VII 1905 Pasiphae VIII 1908 Sinope IX 1914 Lysithea X 1938 Carme XI 1938 Ananke XII 1951 Leda XIII 1974 Thebe XIV 1979 Adrastea XV 1979 Metis XVI 1979 Callirrhoe XVII 1999 Themisto XVIII 2000 Megaclite XIX 2000 Taygete XX 2000 Chaldene XXI 2000 Harpalyke XXII 2000 Kalyke XXIII 2000 Iocaste XXIV 2000 Erinome XXV 2000 Isonoe XXVI 2000 Praxidike XXVII 2000 tbn S/2000 J11 2000 Autonoe Jupiter XXVIII 2001 Thyone Jupiter XXIX 2001 Hermippe Jupiter XXX 2001 Eurydome Jupiter XXXII 2001 Sponde Jupiter XXXVI 2001 Pasithee Jupiter XXXVIII 2001 Euanthe Jupiter XXXIII 2001 Kale Jupiter XXXVII 2001 Orthosie Jupiter XXXV 2001 Euporie Jupiter XXXIV 2001 Aitne Jupiter XXXI 2001 tbn S/2002 J1 2002 tbn S/2003 J1 2003 tbn S/2003 J2 2003 tbn S/2003 J3 2003 tbn S/2003 J4 2003 tbn S/2003 J5 2003 tbn S/2003 J6 2003 tbn S/2003 J7 2003 tbn S/2003 J8 2003 tbn S/2003 J9 2003 tbn S/2003 J10 2003 tbn S/2003 J11 2003 tbn S/2003 J12 2003 tbn S/2003 J13 2003 tbn S/2003 J14 2003 tbn S/2003 J15 2003 tbn S/2003 J16 2003 tbn S/2003 J17 2003 tbn S/2003 J18 2003 tbn S/2003 J19 2003 tbn S/2003 J20 2003 tbn S/2003 J21 2003 tbn = to be named List of moons for all planets »»

Galilean satellites. Jupiter's best known moons are the four large planet-sized bodies — IO, EUROPA, GANYMEDE, CALLISTO, and AMALTHEA. They are known as the Galilean satellites because they were seen first in 1610 by the astronomer Galileo Galilei.

Ganymede is the largest moon in the Solar System, with a diameter of 3,260 miles. On the other hand, the recently-discovered moons are tiny, just a mile or so across.

The little bodies orbit Jupiter at distances of tens of millions of miles from the giant planet. Astronomers discovered them in 2003 using the world's two largest digital cameras — the Subaru Telescope and the Canada-France-Hawaii Telescope, both atop Mauna Kea in Hawaii.

The numerous small outer moons — which may be asteroids captured by the giant planet's gravity — hardly resemble the Galilean satellites. The outer moons are much smaller, with estimated diameters between 1.2 and 2.4 miles. They are much farther away — some 12 million miles from Jupiter traveling highly eccentric retrograde orbits opposite the direction that Jupiter rotates.

The moons travel in clusters and may well be pieces of larger objects that shattered in collisions with passing comets. Jupiter may have captured the many small objkects during its infancy in the first million years of the Solar System. One possibility is that the planet's atmosphere slowed passing asteroids enough to hold onto them. Or maybe Jupiter grew so rapidly in its early days that it trapped nearby objects.

Miniature Solar System. Jupiter is the most massive planet in our Solar System. With its numerous moons and rings, the Jupiter system resembles a miniature Solar System.

The planet itself is like a small star. If Jupiter had been fifty or a hundred times more massive, it would have become a star rather than a planet.

Jupiter's rings surprised astronomers when they were discovered by the Voyager-1 probe in 1979. Jupiter's system of rings apparently relates to the planet's many moons. The rings seem to have been formed by dust kicked up as interplanetary meteoroids smashed into the giant planet's four small inner moons.

Both the flat main ring and an inner cloud-like ring called the halo are composed of small, dark particles. The main ring probably comes from the tiny moon Metis.

A third "gossamer ring" looks transparent. Upon closer inspection, it turns out to be three rings of microscopic debris kicked up by three small moons — Amalthea, Thebe and Adrastea.

Is There An Ocean Inside Callisto?

The most heavily cratered body in the Solar System may have a vast water ocean indside.

Jupiter's large moon Callisto is the outermost of four large jovian natural satellites. It appears to have been rocked in ancient times when some large object — possibly an asteroid or comet — crashed into an area known today as the Valhalla Basin.

The Galileo probe, which has been traveling around Jupiter's system of planets since 1995, has sent back to Earth new close-up pictures of the side of Callisto directly opposite the Valhalla Basin.

The back side of the moon shows no effect from the impact on the other side at Valhalla Basin, according to NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory. That probably means that an underground ocean cushioned the blow of the impact.

Other bodies of our Solar System, such as the planet Mercury and Earth's Moon, have similar impact basins. However, unlike Callisto, they have grooved hilly terrain on the back side attributed to intense seismic shocks from collisions with large objects. Unlike Callisto, they did not have underground reservoirs to soften a blow.

Galileo snapped the Callisto photographs opposite Valhalla Basin in May 2001 as it flew within 20,000 miles of the icy, rocky moon. Callisto, with a surface of ice and rock, is the most heavily cratered of any moon in our Solar System.

The new discovery echoes a theory put forth in the 1990s bu astronomers who suggested that a liquid layer inside Callisto could cushion collisions on the exterior.

Callisto was discovered along with Io, Europa and Ganymede in 1610 as astronomer Galileo Galilei was skygazing from his garden in Padua, Italy. He was surprised to see four small "stars" near Jupiter. They turned out to be Jupiter's four largest moons known collectively today as the Galilean satellites.

Learn more: Oceans may harbor life on Jupiter's moons »»

Io is Peppered With Hundreds of Volcanoes

Jupiter's sulfurous moon Io is the innermost of the giant planet's four largest moons and the most volcanic world in our Solar System. In fact, Io is peppered with hundreds of volcanoes, several of which might be active at any given moment.

NASA engineers sent the Galileo spacecraft on a close encounter with the north pole of Io on August 6, 2001, to take unprecedented magnetic measurements and to examine the site of a recent volcanic eruption.

Galileo sped across an area of Io called Tvashtar at an altitude of only 200 km.

That area had been seen belching a giant plume of volcanic gases only seven months before. Scientists hoped the volcano might still be active so Galileo could fly right through a volcanic plume for the first time.

Volcanic plumes in Io's polar regions don't show up often and then are short-lived. When they assigned the task to Galileo, the scientists didn't know whether the Tvashtar volcano would be erupting or not.

Tides make Io fiery. Of course, those are not like ocean tides on Earth. Rather, they are tidal bulges in the solid crust of the moon Io. Jupiter's gravitational field and the gravitational fields of its other large moons raise the bulges on Io as high as a 30-story building.

The bulges move as Io orbits the giant planet. Io's crust flexes and heats the moon's interior. That is the source of energy for volcanoes that seem to constantly spew lava.

Galileo also conducted two close flybys of Io in 1999 to study and photograph that moon's intense volcanic activity.

In 2001, Galileo went dashing through the snows of Io. As the spacecraft flew past the north pole of the moon, it sailed through a swarm of sulfurous snowflakes hurled into space by a previously uncharted volcano. Scientists who had not expected the probe to encounter fresh volcanic ash were delighted.

Galileo also photographed a slumping cliff, migrating eruptions and churning lava lakes on Jupiter's sizzling moon.

Learn more: Volcanos active on Jupiter's moons »»

Buried Oceans of Warm Slush on the Moon Europa

Researchers concentrated a lot of effort on Jupiter's intriguing moon Europa. The images from Galileo suggest that Europa's icy surface hides a layer of warm slush or even liquid water. That would make it the only place in the Solar System, other than Earth, known to have that life-sustaining liquid.

Galileo swooped by the intriguing moon eight times during the first 14 months of its 24 month extension. One close encounter came in December 1997 when the spacecraft flew 124 miles above Europa's surface.

Europa images of Europa showed areas never seen before, covered with features that support the notion of a buried ocean. Structures that now look like giant blisters may have been formed as warm material welled up inside Europa, like giant blobs within a lava lamp. Natural heat inside Europa, from radioactive minerals and from the friction of being tugged around by Jupiter's gravitational pull, might keep Europa warm enough for its interior to be molten.

Some of Galileo's pictures make it look like the lava-lamp blobs might have carried minerals toward the moon's surface. Instruments aboard Galileo have found areas where magnesium and sulfate-rich salts are concentrated. Such evidence suggests that Europa was once partly liquid, but the timing of those ancient events is unknown. For researchers, the question is, has Europa's core been warm throughout geological history?

Some astronomers suggest Europa has been active geologically during the recent several million years. Others claim it has been quiet for at least 3 billion years.

Europa's ice crust is two miles deep. Impact craters on the moon show that its brittle ice shell crust is more than 1.8 to 2.4 miles thick.

Lava lamp. Galileo scientists suggested in 2002 that giant spots that look like red freckles on Europa might be geologic "elevators" carrying microbial life from a subterranean ocean to the icy surface of the moon.

That means Europa acts somewhat like a big lava lamp, transporting material from near the moon's surface down to the submerged ocean, while transporting organisms up toward the surface.

The red spots appear to be about six miles wide in Galileo images.

The ruddy patches are similar in shape and size, which suggests that warm ice and slush from the interior of the moon churn up to the surface even as colder ice chunks sink down from the surface.

The freckles were found in high-resolution observations from two Galileo flybys of Europa. Other Galileo images offered evidence that a vast ocean exists miles under the satellite's icy exterior. Scientists suspect that liquid reservoir may offer the environmental conditions necessary to sustain life such as primitive microbes.

Rather than drill 13 miles down through the ice, a robot lander on Europa could sample material just below the surface in one of the ruddy spots. Slush might be warm enough for organisms to survive just a mile beneath the surface.

Learn more: Oceans may harbor life on Jupiter's moons »»

Ganymede Has Its Own Magnetic Field

Ganymede — the largest moon of Jupiter and, in fact, the largest moon in the Solar System — has its own magnetic field. Internal tidal friction has some surprising effects on the big moon.

Even though it only is a moon of Jupiter, Ganymede is larger in diameter than the planet Mercury, although only about half its mass. Ganymede also is much larger than the planet Pluto.

The Galileo spacecraft exploring the area around Jupiter revealed that Ganymede has its own magnetic field. The stirring of its molten core of iron sulfide may have generated the magnetic field. Perhaps having been in a slightly different orbit in its past, enough heat from tidal friction may have caused a separation of material inside Ganymede.

Ganymede's surface seems to have two kinds of terrain — very old, highly cratered dark regions and somewhat younger, although still ancient, lighter regions with extensive grooves and ridges. Evidence of a thin oxygen atmosphere may have been found in Hubble Space Telescope images of Ganymede.

Learn more: Magnetic fields and Jupiter's moons »»

Galileo's Final Observation:

A Featherweight Jumble Named Amalthea

To prevent contamination of Europa when Galileo came to the end of its working life, NASA steered spacecraft to crash into Jupiter in 2003.

Before the end, the aging spacecraft made a final pass over the tiny inner moon Amalthea inside Jupiter's dangerous radiation belts. Galileo passed within 99 miles of the moon on November 5, 2002.

Amalthea was the last moon to be discovered by direct visual observation — as opposed to photography — when it was spotted in 1892 by Edward Emerson Barnard using the 36 inch telescope at Lick Observatory on Mount Hamilton in California.

Amalthea radiates more heat than it receives from the Sun, probably as a result of electrical currents induced inside the small body by Jupiter's magnetic field.

Potato moon or pile of rubble? NASA's Galileo spacecraft continued to deliver surprises with the discovery that Jupiter's red-tinted, potato-shaped inner moon, Amalthea, has a very low density. That means it is full of holes. In fact, Amalthea may be just a loosely packed pile of rubble."

The gaps between chunks seem to amount to more of the moon's total volume than the solid pieces. Amalthea probably is mostly rock with a little ice mixed in, rather than a mix of rock and iron.

This tiny moon is only 168 miles long and half that in width. Amalthea's density is about that of water ice.

What holds it together? Amalthea's irregular shape and low density suggest the moon has been broken into many pieces that now cling together from the pull of each other's gravity, mixed with empty spaces where the pieces don't fit together tightly. It's probably boulder-size or larger pieces just touching each other, not pressing hard together.

Planetary scientist now wonder if the mini moon does not have enough mass to pull itself together into a spherical body like Earth's Moon or Jupiter's four largest moons.

Chips off the old block? Serendipitously, Galileo discovered seven to nine space rocks near Jupiter's inner moon Amalthea as the spacecraft flew past at the end of 2002.

The probe's star scanner detected the objects as nine bright flashes of light during the flyby. Two of the recorded flashes may have been duplicate sightings.

The star scanner is a telescope aboard Galileo used to determine the spacecraft's orientation by sighting stars. Information from the scanner was recorded by Galileo's tape recorder during the flyby and later transmitted to Earth. Experts at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Pasadena, California, analyzed the data to estimate the sizes of the objects, which seem to have ranged from gravel to stadium-size boulders.

The seven or nine tiny bodies might have been drawn by gravity into an orbit near Amalthea or they may have been split off of the moon as a result of past collisions with other objects.

Galileo from Beginning to End

Galileo left Earth aboard NASA's space shuttle Atlantis in 1989. It began orbiting the giant planet Jupiter on December 7, 1995. It was ordered to end its life by flying down into Jupiter's atmosphere on Sept. 21, 2003.

The spacecraft had just about depleted its supply of propellant needed for pointing its antenna toward Earth and controlling its flight path. While still controllable, the probe has been put on a course for impact into Jupiter to prevent Galileo from drifting into an unwanted impact with the moon Europa, where the spacecraft had discovered and sent back evidence of a subsurface ocean that might be a habitat for extraterrestrial life.

Close call. After more than seven years of exploring around Jupiter, the Amalthea encounter was Galileo's last flyby of a jovian moon. The last flyby brought Galileo closer to the planet Jupiter than at any time since it had flown into orbit around the giant planet. After more than 30 close encounters with Jupiter's four largest moons, the Amalthea flyby was the last for Galileo.

NASA JPL. NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), a division of the California Institute of Technology (Caltech) in Pasadena, California, managed the Galileo mission for NASA's Office of Space Science, Washington, D.C.

Source: NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory

Solar System Search STO STO cover Questions Feedback Suggestions © 2004 Space Today Online