|

||||

| Mercury | Messenger | BepiColombo | Resources | Planets |

The Planet Mercury:

MESSENGER Explores the Planet Nearest the Sun

Learn more about the planet Mercury »»

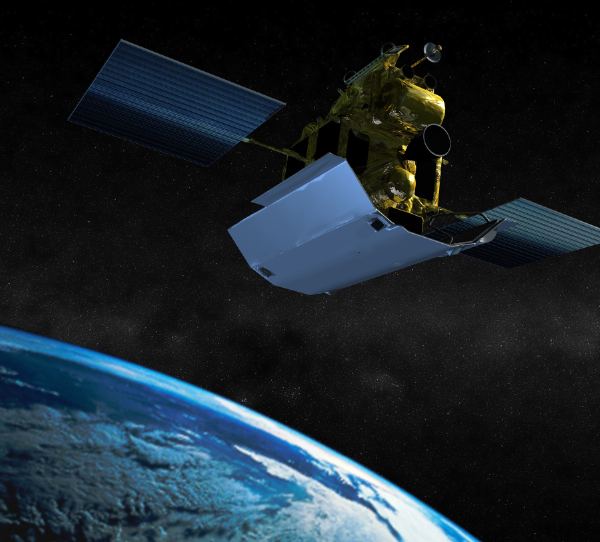

Artist's view of the interplanetary probe MESSENGER leaving Earth after launch from Cape Canaveral, Florida, aboard a Delta 2 rocket. Click to enlarge image from NASA/Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory/Carnegie Institution of Washington.

Artist's view of MESSENGER arriving at Mercury. The probe's instruments operate at room temperature behind a sunshade of heat-resistant ceramic fabric despite the heat from the Sun, which is up to 11 times brighter at Mercury than Earth. While Mercury's surface temperature reaches 840°F, MESSENGER will pass only briefly over the hottest areas of the surface, limiting exposure to heat re-radiated from the planet. Click to enlarge image from NASA/Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory/Carnegie Institution of Washington.

Previously unseen side of Mercury. MESSENGER became the first spacecraft to see this side of Mercury. This was the first image transmitted to Earth following the flyby of Mercury. The image was recorded by the spacecraft's wide angle camera. Above and left of center is a small crater with a pronounced set of bright rays extending across the planet's surface away from the crater. Bright rays are commonly made in a crater-forming explosion when an asteroid strikes the surface of an airless body like the Moon or Mercury. But rays fade with time as tiny meteoroids and particles from the solar wind strike the surface and darken the rays. The prominence of these rays implies the small crater at the center of the ray pattern formed recently. This image is from NASA/Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory/Carnegie Institution of Washington.

Different area of Mercury's surface. MESSENGER's narrow-angle camera captured this image during the January 2008 flyby. The Sun is illuminating the region at a low angle, accentuating the modest ridges and other low topography on the nearly flat plains. Low ridges trend from the top-center of the image to the left edge (white arrows). The ghostly remains of craters are visible, filled to their rims by what may have been volcanic lavas (red arrows). The faint remnant of an inner ring within the large crater in the bottom half of the picture can be seen (blue arrow); the area interior to this ring was also flooded, possibly by lava, nearly to the point of disappearance. Clusters of secondary craters on the floor of the large crater and elsewhere (yellow arrows) formed when clumps of material were ejected from large impacts beyond the view of this image, which is about 220 miles (350 kilometers) across. Click to enlarge this image and see the colored arrows. This image is from NASA/Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory/Carnegie Institution of Washington.More images:

The Great Caloris Basin on Mercury »

"The Spider" Radial Troughs within Caloris »

Mercury Shows Its True Colors »

MESSENGER mission postage stamp issued May 4, 2011, by the United States Postal Service (USPS) commemorates the day of March 17, 2011, when MESSENGER became the first spacecraft to enter orbit around Mercury.

After a 2 billion mile cruise and three and a half years, NASA's MESSENGER spacecraft flew within 124 miles of of the planet Mercury on January 14, 2008, pulling itself onto a path that will lead it to orbit our Solar System's innermost planet in 2011.

The MESSENGER flyby was the first visit by a spacecraft to Mercury in three decades.

It took 10 minutes for radio signals from the small interplanetary probe to reach Earth and the flight controllers at Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory in Laurel, Maryland.

The close approach was necessary for MESSENGER to pick up a gravity assist from Mercury in order to enter orbit around the planet in 2011.

The last and only time a spacecraft flew past Mercury was NASA's Mariner 10 probe in 1975. It mapped about 45 percent of Mercury's surface.

The 2008 flyby. It was the first of three planned MESSENGER flybys of Mercury.

On January 14, 2008, MESSENGER passed within 125 miles (200 km) of Mercury's surface - much closer in than Mariner 10, which had passed within 435 miles (700 km) of the surface.

MESSENGER pointed instruments at Mercury that are far more advanced than those of the previous probe back in the Apollo era.

Unlike Mariner 10, MESSENGER eventually will stop and stay a while, settling into orbit in 2011.

However, before that, it will make two more flybys of Mercury – in 2008 and 2009. The probeÕs trajectory will bring it to a second Mercury flyby on October 6, 2008.

The name MESSENGER is an acronym for MErcury Surface, Space ENvironment, GEochemistry, and Ranging. The probe was launched from Earth in August 2004.

Seeing it all. In the 2008 flyby, MESSENGER photographed the planet closer and in more detail than ever before. The spacecraft's cameras and sensors collected 1,213 images and made the first up-close measurements since Mariner.

The photos it sent back revealed what seems like an extreme version of Earth's Moon, with craters inside craters, inside craters.

Mercury rotates slowly, which left one side of the planet turned away from the earlier passing probe. As a result, until now, we've known only what poor-quality Earth-based telescopes showed us of other areas of Mercury, as it constantly passes in front of the blinding light of the Sun.

In the first 2008 flyby, MESSENGER sent home surprising new information about Mercury. The data included a weird crater nicknamed "the Spider," measurements that show he planet's giant Caloris basin is even bigger than researchers imagined, and a planetary tail of hydrogen atoms.

The Spider. Researchers had expected Mercury to be like Earth's Moon, but MESSENGER found some differences. For instance, unlike our Moon, Mercury has huge cliffs with structures snaking hundreds of miles across the planet's face.

The spacecraft also spotted impact craters that appear to be quite different from lunar craters. One particularly curious crater has been nicknamed "The Spider."

The Spider is in the middle of a huge impact crater called the Caloris basin and seems to be composed of more than 100 narrow, flat-floored troughs radiating from a complex central region. The Spider has a crater near its center, but whether that crater is related to the original formation or came later is not clear.

When Mariner flew by Mercury, it saw only a portion of the Caloris basin. Now, MESSENGER has shown the basin's full extent.

The Caloris basin diameter has been revised upward from the Mariner 10 estimate of 800 miles to perhaps as large as 960 miles rim-to-rim. It is one of the largest impact craters in the Solar System.

MESSENGER eventually will see all of the planet including the opposite side of the planet, which has not been observed before by a spacecraft.

Magnetic cocoon. MESSENGER found Mercury's magnetic field to be different from the Mariner observations. While the planet's magnetic field was quiet with no magnetic storms uerway as MESSENGER passed by on, it showed signs of significant internal pressure.

It will be measured again during additional MESSENGER flybys in 2008 and 2009 and the yearlong orbit of the planet beginning in 2011.

Atomic tail. MESSENGER's instruments also detected ultraviolet emissions from sodium, calcium and hydrogen in Mercury's exosphere.

An exosphere is a super-low-density atmosphere probably formed, in this case, from atoms sputtering off Mercury's surface. The sputtering may be caused by contact with hot plasma trapped in Mercury's magnetic field.

MESSENGER encountered Mercury's sodium-rich exospheric "tail" which extends more than 25,000 miles from the planet.

The probe also discovered a hydrogen tail of similar dimensions.

Mysteries to be solved. What are scientists on the lookout for? MESSENGER will scan Mercury to find out:Other flybys. On its way to becoming the first spacecraft from Earth ever to orbit the planet Mercury, the probe flew by the planet Venus twice and Earth once to pick up additional gravity assists that propelled it deeper into the inner Solar System.

- if there is ice at the bottom of Mercury's polar craters, which never see the scorching 450 C heat of Mercury's day side

- whether so-called Vulcanoids, a theoretical swarm of asteroids hidden in the glare of the Sun, exist further inward towards our star

- whether Mercury has an atmosphere or not since hydrogen and helium floating above the planet may just be captured by the Sun, although there's a possibility that gasses sometimes evaporate from near Mercury's surface

- what makes Mercury the densest planet in the Solar System

- whether or not Mercury is shrinking. Could 100-km.-tall ridges on the surface be a sign the planet is buckling under a slow implosion?

It swung by Earth in August 2005, then past Venus in October 2006 and again by Venus in June 2007.

At Earth. When the spacecraft swooped around Earth in 2005, it approached to within 1,458 miles of our planet over central Mongolia.

Earth's gravity tugged at MESSENGER, changing its trajectory significantly. After the flyby of Earth, the probe's average orbit is some 18 million miles closer to the Sun. The maneuver at Earth sent MESSENGER toward the planet Venus where it will receive another gravity-assist from a flyby in 2006.

A year later. The Earth flyby came just one day short of a year after it's launch. The 2,425-lb., solar-powered spacecraft was launched August 3, 2004, on a Boeing Delta 2 rocket from Cape Canaveral Air Force Station, Florida.

MESSENGER mission controllers at the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory (APL) at Laurel, Maryland, said the spacecraft is performing flawlessly. They used the probe's close proximity to Earth during the flyby to calibrate science instruments aboard MESSENGER.

As it approached Earth, the spacecraft's atmospheric and surface composition spectrometer made several scans of the Moon along with photographic observations. In addition, the particle and magnetic field instruments spent several hours measuring Earth's magnetosphere.

MESSENGER's main camera snapped several shots of Earth and the Moon, including a series of color images, beginning with South America and continuing for one full Earth rotation.

Earth from 655,570 miles on July 30, 2005 » APL news release »

Looping inward. As it looped around Earth, the probe was approximately 581 million miles into its 4.9 billion mile voyage that will include 14 more loops around the Sun before it flies into orbit around Mercury.

MESSENGER will fly past Mercury three times on its way to orbit there.

The Mercury flybys in January 2008, October 2008 and September 2009 will help MESSENGER match that planet's speed. These events will set up a maneuver in March 2011 that will start a year-long science orbit around Mercury.

At Venus. The Venus flybys also were designed to perfect MESSENGER's path to the innermost planet.

During the first flyby, in October 2006, no scientific observations were made because the cloud-shrouded planet was on the opposite side of the Sun from Earth and radio signals could not be received from the probe. Its closest approach was some 1,800 miles above the planet's surface.

During the second Venus flyby, in June 2007, all of MESSENGER's seven scientific instruments were turned on simultaneously for the first time. Scientists tested and calibrated them in preparation for the first Mercury flyby in January 2008.

Messenger approached Venus's daylight side at a speed of more than 30,000 miles per hour, passed over the boundary line between day and night, and passed just 200 miles above of the planet's night side surface.

The planet's gravity slowed MESSENGER from 22.7 to 17.3 miles per second.

During the 73-hour flyby of Venus, MESSENGER stored more than 600 images of the planet and collected more than six gigabytes of data about Venus' atmosphere, cloud structure, space environment and surface.

MESSENGER also carried out joint observations with Europe's Venus Express probe currently in orbit around Venus. The two spacecraft worked together studying how the Sun's solar wind particles affect the upper layers of Venus's atmosphere.

Exploring Mercury. Mercury is the least explored of the of the Solar System's innermost terrestrial planets that also include Venus, Earth and Mars.

Earth and Mars have moons. Mercury and Venus do not.

MESSENGER will conduct the first orbital study of Mercury. Its mission is to map the entire planet and send home information about the planet's geologic history and its composition and structure including its core and poles.

During one Earth year – four Mercury years – MESSENGER will send home the first images of the entire planet. The probe will collect and send to Earth detailed information about the composition and structure of Mercury's crust and the nature of its atmosphere and magnetosphere.

The journey. The Earth, Venus and Mercury flybys are designed to slow down the spacecraft as it falls in toward the Sun. Eventually, it will be travelling slow enough that the planet Mercury can capture it as it flies by in 2011.

During the last flybys of Mercury, the probe will send home data that will be used back on Earth for planning the year-long orbit.

After a journey of 4.9 billion miles, including 15 trips around the Sun, MESSENGER will fly into orbit around Mercury in March 2011.

It will send back science information during those numerous Venus and Mercury flybys and then for a year from its orbit around Mercury.

Science suite. MESSENGER is carrying seven science instruments to photograph and study Mercury. They will be used to:What do we want to know? MESSENGER has an ambitious science plan. Some of the science questions to be answered by MESSENGER's seven miniature instruments are:

- determine Mercury's composition

- image its surface globally and in color

- map its magnetic field

- measure the properties of its core

- explore mysterious polar deposits to learn whether ice lurks in the shadows

- characterize the Mercury's tenuous atmosphere

- describe the planet's Earth-like magnetosphere.

- What is Mercury's tectonic history?

- Is Mercury's surface shaped by volcanism?

- What is the origin of Mercury's high density?

- What is the nature of the mysterious polar caps?

- What are the composition and structure of its crust?

- What are the characteristics of the thin atmosphere?

- What is the nature and origin of Mercury's magnetic field?

- What are the characteristics of Mercury's small magnetosphere?

Recent radar observations from Earth, reported in 2007, have shown that Mercury has a molten core. Once, scientists had thought the planet had a solid iron core until the interplanetary probe Mariner 10 discovered in 1974 that Mercury has a weak magnetic field, which indicated a molten core.

Some things we already know. Here are some things we already know about the planet Mercury:

Terrestrial Planets

Mercury is one of nine known major planets of the Solar System.

Mercury is closest to the Sun.

The others in order outward are Venus, Earth, Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, Neptune and Pluto.

The four inner planets – Mercury, Venus, Earth and Mars – are rocky metallic bodies.

They are referred to as terrestrial planets since they are much like our own planet Earth.Scientists say that understanding Mercury and the forces that shaped it will help us understand the evolution of all of the terrestrial planets like Earth.

- Mercury's density is the highest of any planet.

- Its exotic atmosphere is the thinnest among all the terrestrial planets.

- It is the only terrestrial planet, besides Earth, to possess a global magnetic field.

- Temperatures on the fire and ice planet vary from nearly the highest in the Solar System, at the equator, to among the coldest, in the permanently shadowed poles where ice deposits seem to lurk.

In a few years, through MESSENGER's science instrument data transmissions, we will see things never before seen and know far more about the formation of the Solar System than we know today, according to Dr. Michael D. Griffin, head of the JHU APL Space Department.

Previous visitor. Previously, Mercury has been visited by only one probe from Earth, Mariner 10, which flew by the planet three times in 1973 and 1974. It mapped only 45 percent of the surface.

Unfortunately, Mercury is too close to the Sun to be photographed safely by today's orbiting observatories such as Hubble Space Telescope.

What's in a name? MESSENGER is a scientific spacecraft built to investigate the planet Mercury. Its name is an acronym for MErcury Surface, Space ENvironment, GEochemistry, and Ranging.

Discovery program. Mercury is the planet closest to the Sun. The first spacecraft from Earth to conduct a study of the Solar System's innermost planet from orbit around that body, MESSENGER is the seventh in NASA's Discovery program of low-cost, scientifically focused missions of Solar System exploration.

Discovery projects are highly-focused, low-cost, quickly-built science spacecraft.

The team. MESSENGER is the seventh mission in NASA's Discovery Program of lower-cost, scientifically focused, exploration projects. The mission is supported by the NASA Discovery Program by contract with the Johns Hopkins University's Applied Physics Laboratory (JHU APL) and the Carnegie Institution of Washington (CIW). JHU APL » CIW »

- The mission is managed for NASA by JHU APL in Laurel, Maryland.

- The spacecraft was designed and assembled at JHU APL. MESSENGER was the 61st spacecraft built at JHU APL.

- The spacecraft is operated during its flight by JHU APL.

- The science instruments were built at:

- JHU APL

- NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, Greenbelt, Maryland

- University of Michigan, Ann Arbor

- University of Colorado, Boulder

- The science team is composed of of investigators from 13 institutions across the U.S.:

- Brown University

- Carnegie Institution of Washington

- Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory

- Massachusetts Institute of Technology

- NASA Goddard Space Flight Center

- Northwestern University

- Southwest Research Institute

- University of Arizona

- University of California, Santa Barbara

- University of Colorado

- University of Maryland

- University of Michigan

- Washington University

- The Science Operations Center (SOC) at JHU APL acquires, manages, and archives MESSENGER science data.

- The Education and Public Outreach Program Team members are from:

- Challenger Center for Space Science Education

- Carnegie Academy for Science Education

- Center for Educational Resources at Montana State University Bozeman

- American Association for the Advancement of Science

- Minority University-SPace Interdisciplinary Network

- National Air and Space Museum

- Goddard Space Flight Center

- Science Systems and Applications, Inc.

- GenCorp Aerojet, Sacramento, California, designed, built and installed the spacecraft propulsion system.

- Composite Optics of San Diego, California, provided the spacecraft's composite structure.

- KinetX of Simi Valley, California, leads the navigation team guiding MESSENGER through the inner region of the Solar System toward its target of orbiting Mercury in 2011.

- NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory, at Pasadena, California, manages the Deep Space Network (DSN) antennas used to communicate with MESSENGER across millions of miles.

- The Delta 2 launch rocket was built by Boeing Expendable Launch Systems.

Read more about the Solar System . . . Star: The Sun Inner Planets: Mercury Venus Earth Mars Outer Planets: Jupiter Saturn Uranus Neptune Pluto Other Bodies: Moons Asteroids Comets Beyond: Pioneers Voyagers